Domestic Labor,

Knitting and alternative networks: Knit++

By imam@xurban_collective

“Space is about potentia(ls) and thus, about liberation, Intensified technological circulation is in itself in need of exploitation of "human/natural resources". Liberty, therefore, can only be exercised as ‘liberation from’ mass-machinery (military/state/corporation)”[1]

xurban_collective is a loosely associated group which composed of artists, designers and scholars. Over the last decade, we have realized numerous projects that questioned governmental technologies, neo-liberal and military exclusion and containment strategies and rapid urban transformation via visual artistic methods. Our artistic production is based on a collective model, which aims to realize issue-based-projects without any financial or social obligations to its members.[2]

In 2002, in order to analyze and compare new and old labor practices and the spatial organization of work, we decided to look at “Knitting” for both its metaphorical and literal implications for the understanding and organization of labor today. As a collective, self-organized online, we decided to realize a website to engage with various issues. Knit++ was a multiuser dynamic website which was composed of a navigation and project space. We considered the project as a small-scale experiment where we could test our ideas about collective production and non-hierarchical collective organization[3]. For us, it was particularly important to recognize and challenge the stratified dichotomies by means of super-impositions of multiple informative layers generated by research and production[4]. In order stay away from the opposition between material/immaterial production, we considered the multiplicity of labor practices about homeworking, knitting and contemporary artistic production altogether on a same surface, which was presented a randomly generated pattern which was produced by specific algorithms.

An exhibition, a catalogue or a journal provides a contextual framework one can rely on. Although, with respect to our initial intentions and the project outcome, Knit++ project can be considered as a “feminist” undertaking. Instead of highlighting a definitive scholarly approach, we decided to challenge our members to come up with their personal strategies to tackle with the issue of that we were exploring. The scope of project was to bring wide range of interdisciplinary approaches on the same artistic plane to create alternative creative assemblages. In similar vein, this paper is not a complete document intended to address the issues in homeworking and domestic labor and conditions of homeworking, but should be considered as a patchwork. I hope that for the critical review of Knit++ for fe journal: feminist critique, will provide necessary backdrop for further feminist inquiries.

Just like any other homeworker, we recognized that artists, scholars and academicians arrange and organize weave, (knit/ lace/ knot) new patterns thus establishing new associations with pictures, videos and words. We compose our ideas and translate them into visually recognizable forms which are eventually distributed; read, seen, stored. We distinguish video-image from photography, text from painting, knitting from a piece of computer programming, yet, we can see that the conditions of waged or unwaged labor, how we all engage with the material world, how we transform raw materials into meaningful clusters evince many similarities. When we engage in these activities, the time that we give, and the places that we work for, the way that we are exploited is not utterly different from each other. In fact, museums, universities, publishing houses and media companies can be understood as modern versions of textile manufacturing shops.

A factory or an office is a forced social space where workers from different backgrounds are put together according to their specializations. They share a common space of production and conditions of work and their effort produces new social realities by establishing new connections. This inevitable socialization in a factory establishes a new network. Workers eat together, drink together, get paid together. Nevertheless, under capital order, most of their organizational efforts are subsumed under various hierarchies. Due to corrupt unions, political parties, never ending internal struggles within the Left, in a sad way; it seems that workers have lost their beliefs in democratic participation. In this respect, homeworkers, like artists, are scattered, un-organized and subjected to exploitation while vulnerable to economic fluctuations and pressed under pecking order. But in order to understand the nature of this exploitation we have to understand the nature of networks; how they are formed, managed and guided so that we can develop our own.

Homeworking: A conceptual Overview

With the development of global communication systems, logistical and transportation infrastructures, geographical sites do not posit a limitation to manufacturers. Various parts of the production line can be distributed globally to increase cost efficiency. The transformation from large-scale, location based, “Fordist “production to “Post-fordist” production entails new forms of flexible assembly methods introduced for business productivity and resourcefulness characterized by the term “just-in-time” (JIT) production—which was initially put forth by Ford Motors Company. JIT was implemented in scale manufacturing by the Toyota Motor Company in the late 1950s to reduce inventory and increase labor efficiency, and therefore eliminate associated extra costs[5]. JIT production necessitated extremely flexible production lines characterized by complete integration of supplier-chain through state-of-the-art electronic operation networks. The final goal of this model was to limit stock—considered as waste—and meet immediate market fluctuations. The development of information networks, effective global communication and service industries made the “global division of manufacturing” feasible even for small scale industries.

Due to global economic restructuring to a market economy, local economies are pressured to adjust to unregulated free market rules. To sustain constant growth demanded by the business segment, they are obliged to open their borders for global capital flows, for direct or indirect investments, and change their managerial, production and consumption legislative frameworks. Within this rapidly condensing milieu, classical production sites have moved to areas where there is an abundance of cheap labor and natural resources without any major obstacles. Previous production sites were abandoned and transformed into ‘post-industrial’ urban compositions and they try to adapt to the new global order by changing their economies towards global service industries.

These new conditions demand new kinds of flexible, mobile, educated, and ultimately replaceable labor, both in the factories and service industries alike. Workers need to be flexible in terms of their specialization as well. The labor force needs to be trained and prepared rapidly for various jobs. Factories are employing “open” management strategies and including their employees into decision-making processes[6]. In certain sectors, workers are no longer just part of a serial production line, but rather they are active investors in the business itself, as they literally invest in their companies through directly and indirectly, for instance in U.S. various retirement plans directly put money in the stocks of the company itself, which forms a mental and financial dependency with the business without serious monetary gains.

Homeworking, Then and Now

“…, if the technology permits such decentralization of the production process, the incidence of subcontracting is likely to be high. In a recent survey of over 3000 manufacturing firms in Malaysia, over a third of all electronics, textile and garment firms were seen to have subcontracted out part of the production work. Interestingly, the larger the firm size, the higher was the incidence of such subcontracting.”[7]

By the late 20th century large mainframe computers --previously could only be owned by big corporations or government agencies-- were replaced by personal computers. The “democratization” of information technologies and the introduction of affordable computing and telecommunication devices radically transformed the notion of workspace. “Working from home”, “telecommuting” and “freelancing” became alternatives to “working on site”, effectively transforming domestic space into an extension of high tech offices integrated within the global economy[8]. Lawyers, designers, architects, artists, IT personal, sales people, even doctors increasingly utilized domestic space as for their outside work[9]. It is common that in order to respond increasing market needs, manufacturers utilize temporary workers and sub-contractors. Among these subcontractors, both in high-tech and traditional industries, homeworkers take a considerable portion of the workload, providing an easy alternative to salary-based work for the companies.

In general homeworking can be categorized according to the method of production, type of employment, level of enterprise and so forth. According to Allen & Wolkowitz homeworking can be a;

“1.Short-term wage work, paid and contracted for the day, week, month or season or for fixed tasks or terms; 2.Disguised wage work, including workers who because they do not work at the employer's premises are not legally considered employees, but whose earnings are derived from piece-work payment or from commissions from one or more related firms; 3.Dependent work in which the worker is wholly dependent upon one or more larger enterprises for credit, the rental of premises or equipment , raw materials and an outlet for the product; and 4.True self-employment, in which the producer owns the means of production and has a considerable degree of real freedom in choice of supplier and outlets. In this last case the producer's livelihood is precarious, but depends upon general market conditions, not specific firms.” [10]

Due to top-to-bottom economic re-structuring, de-regulation and open borders for capital flow, national economies are embedded into global markets. In order to preserve their competitive edge and capital influx, these export-oriented countries maintain their work legislations to keep their “labor costs” at the lowest levels possible. In fluctuating economic waters, various industries tap into homeworkers as reserve industrial workers. Homeworking practices are extremely suitable for global manufacturers as they provide many financial advantages: they do not require production space, warehousing, lighting, cleaning, maintenance, manufacturing equipment, insurance and environmental control; all of which are provided by the homeworkers themselves. However, homeworkers are the first ones who are affected by an economic overturn. The International Labor Organization’s report states that during the Asian economic crisis in the 90s;

Homeworkers are among the more vulnerable segments of the workforce, as they are generally outside the scope of protective labor legislation and social security systems. They have precarious income sources. They wield little bargaining power vis-à-vis contractors and their principals and agents, and because they often perform their work within the confines of their homes and are socially invisible and unorganized. In the global economy, the incidence and spread of home work as a form of production and employment relationship has become marked as homeworkers form part of the global decentralized production system.[11]

Due to the nature of work characterized by current demands, a high turnover rate makes it hard to obtain salient figures that represent homeworking. There is no effective data about homeworkers’ contribution to the global economy either, “however certain indicators do exist to show that homeworking is contributing significantly to export earnings in many countries in recent times.”[12] Developed countries gather this data specifically for tax purposes but not necessarily for well-beings of homeworkers[13]. In hard times, they are usually left alone without any social security benefits as they are considered self-employed “entrepreneurs”.

Since regulation is kept to a minimum, homeworking has become an “effective” way of governing the efficiency of work since contracts done by piece-work which includes quality control and organization. If the worker is not suitable for the job, the relationship is quickly cut without any financial weight on the employer. Furthermore, homeworking usually has no definitive work hours, as it can easily extend into nights and weekends. It has unpredictable, usually low wages and workers are left without any health benefits if they do not cover the cost of social security or insurance themselves. Homeworkers are required to do their own accounting and fulfill many managerial functions at once in addition to meeting required deadlines. For the middle man, the main way of controlling the quality of work produced is the refusal to pay for any work not up to standard, and corrections have to be made in the homeworker's own time. [14]

Working from home is not a new phenomenon. In fact, prior to the drastic separation between domestic and public space, “homeworking” was the common means of production. In agrarian societies home was the space for constant production, consumption, entertainment and leisurely activities. The Industrial Revolution ignited the break between the home and public space based on the sexual division of labor[15]. Charged with a new morality, the bourgeoisie gradually separated their homes from their workspace and distanced themselves from domestic laborers; i.e. men went to “work”, women and children stayed at “home”[16]. Nevertheless, in addition to their responsibilities at home, domestic laborers engaged in wide range of direct and indirect industrial activities and participated in markets from home including textile, agriculture, catering and child care industries. In this respect, both the domestication of traditional wage jobs and the professionalization of domestic labor challenges classical conceptions of the productive/unproductive labor dichotomy presented by both Liberal and Marxist theories. These theories usually did not consider working at home because of the nature of the work itself, which cannot directly be measurable in “value”, “surplus” or “profit” terms[17]. In other words, homeworking (working for wage) and domestic labor (working without any wage) cannot be distinguished from each other as time and space of production spills over onto each other. Paid and unpaid work-time overlap and becomes extremely complicated when we specifically consider women’s domestic labor in its totality. Unpaid works such as cleaning home, cooking, other housework activities and most importantly reproductive labor and child care requires constant work alongside “productive” works for the market. When industrial process spills over to the domestic sphere, a woman’s body becomes a site for total exploitation. Normative biomedical conception of a woman’s body is characterized by conservative family values and designates not only specific gendered division of labor and patriarchal control of reproductive power, but also various forms of capitalist processes which directly aim to capsulate creative women labor within the domestic sphere. The “invisibility of women workers” from the work force hides the heterogonous “productive” activities that women conduct in day-to-day operations.[18] Homeworking in that respect slips from liberal egalitarian policies, which aim to guarantee women’s participation in the workspace through various affirmative action policies. However these liberal policies fail to recognize gender equality in the domestic work environment.

Material / Immaterial

Furthermore, homeworking needs to be critically reconsidered in regard to the problematic division between material and immaterial labor as well. The dichotomy between material and immaterial labor (productive and unproductive labor) is also visible when we look at the creative industries, especially in “audio-visual production, advertising, fashion, the production of software, photography and cultural activities”. In this regard;

“The activities of this kind of immaterial labor force us to question the classic definitions of work and the workforce, because they combine the results of various different types of work skill: intellectual skills, as regards the cultural-informational content; manual skills for the ability to combine creativity, imagination, and technical and manual labor; and entrepreneurial skills in the management of social relations and the structuring of that social cooperation of which they are a part.” [19]

In “immaterial labor”, Lazzarato utilizes a generalized conception of labor to rehabilitate Marx’s binary division between material and immaterial production. Immaterial labor designates the formation of subjectivities in a post-industrial world, where, according to Lazzarato, capitalist “command and control” establishes its order with the least amount of work, effectively and efficiently. Lazzarato analyzes the new subjectivation processes according to the logic of neo-liberal transformation in Europe and elsewhere. He states that neo-liberal policies aim to creating a subject-citizen who is totally dependent on market processes. For instance, artists, need to be creative, have to produce their own work, do their own marketing, network with other professionals, transport their work to art fairs and museums, and also they has to apply to various funding bodies in order to continues their work to be viable in the “art business”. Funding of cultural production acts as an instrumental apparatus in adapting workforce/labor/artists to the global competitive environment and has economical return in the long run for the service oriented markets. In this respect, the funding of creative culture industries and arts needs to be analyzed more like subsidies given to agriculture or high tech/military industries, not “piece-works” given to homeworkers.

The contemporary definition of creative culture industries implies that culture is no longer regarded as a broad characteristic of society, but rather considered as an area of extreme specialization. Policy makers of cultural production need to justify their actions according to rationalized calculable monetary and social-political returns. This rational logic, defies the traditional conception of the aesthetic appreciation of art. Furthermore, when we analyze these processes, we need to problematize the notion of creativity and intellectual labor, through which they are actively subsumed under neo-liberal industrial processes, and “real creativity” which is inherent in all human existence and forms the “social bios”, is re-capsulated under production and distribution processes. Art-making as a process is becoming more and more technologically advanced and an artist’s position in society shifts as they become specialists of technical visual (re)production. In these respects, working from home as a textile worker for a multinational fashion company is not radically different from a computer artist working for a game company; workers needs to know their trade, organize their time and space, do their accounting, and understand market fluctuations in order to provide the most competitive rates.

Furthermore, the introduction of personal computing devices is comparable with the introduction of small sewing machines in the second half of 19th century[20], both have drastically transformed the capabilities of homeworkers. For instance, before the introduction of sewing machines, homeworkers utilized inefficient manual methods which were time consuming and usually not precise. Manual labor was not competitive against industrial manufacturing within a high paced market environment. When small sewing machines became widely available, homeworkers could produce more effectively and they could be directly integrated to a wider industrial production line and supply-chain networks.

Carpet weaving, knitting, embroidery and sewing, are still some of the most common homeworking activities especially for women and they play an important economic role specifically for developing economies. For example in Iran, there are approximately 6 million people directly related with the carpet industry and 90 percent of them are women[21]. In general, women do this work in their private homes and men handle public transactions, negotiate with carpet dealers and handle the money[22]. In this respect industries smoothly tap into home for its patriarchal division of labor and utilize already stratified positions within the family. This posits a direct contradiction with the industrial factory. In contrast to home, the factory presents a “rationalized/modernized” workspace where women’s work is part of the larger (sometimes unionized) labor processes, which inevitably shifts women’s roles in the market space. Inequalities in the industrial space can be clearly identified in modern calculative rational logic by looking to accounting practices and corporate hierarchies, yet the fusion of material/immaterial production in the domestic sphere defies this form of calculative logic. Domestic work becomes only visible when the product from the domestic sphere meets the marketplace.

Developing Alternatives: Is knitting a possibility?

Pessimism is not a salient strategy for a new future; we need more confidence about our creative capacities, sometime a naïve belief is required for developing new possible conditions. We need to look for novel alternatives, develop innovative tools and methods, create unconventional usages of existing techniques, and challenge pre-given models, most importantly we need to work together. We have to recognize that given rule-sets (laws, protocols, moral codes) are meant to sustain the reproduction of existing structures; through these various moral and legal codes, control and command (such as patriarchy) is replicated, distributed and constantly presented as new (neo-liberal logic). We cannot simply rely on pre-given social structures to develop alternatives, i.e. any attempt within family, factory, corporation and state structure has a high possibility to be subsumed for preservation the status-quo. In short, developing new forms of associations requires alternative technical/social procedures. Within this line of thought, in Knit++ project, the idea of “knitting together” was taken as a metaphor for producing a different sociality, forming a diverse network. We simply wanted to experience developing and presenting a new possibility.

Knitting is a visual activity, a method, and a program through which one turns a thread or yarn into clothing, forming a smooth visual surface that eventually warms somebody. The act of knitting, sewing, lacing and embroidering takes a lot of time and a meticulous effort, knot after knot, loop after loop, one has to pull stitches in correct order in order to produce a well executed surface. It requires knowledge, and traditionally this know-how (shapes, patterns, stitches) is passed from one person to another as part of oral traditions[23]. However when knitting is part of a globalized system of transfer, it becomes standardized, patterns are homogenized across the board. Jobs are given by the employer, results are expected to be precise to fulfill the needs of a fictional global customer, an average statistical entity in the need for new products. At this moment, an artist becomes a wageworker, subsumed under economic order, exploited by multinationals.

How can we develop new forms of organization? Does new technological frameworks present an alternative? Is it possible to form an option within the Internet against social hierarchies? These common questions in mind, we try to identify and activate a potential. However we recognize that the Internet inherits hierarchies and it replicates, redistributes and eventually creates new orders. Corporations, companies, governmental agencies, ISPs (internet service providers) are constantly policing the content for one reason or another. Furthermore, the Internet is governed by regulations and protocols usually set by governments and telecommunication companies and there are many technologies, employed in large scale, are used to monitor daily activities. For instance, Turkish and Chinese government actively censuring the Internet by means of centralized command and control. Multiuser websites, which are used by millions, such as YouTube, are being persistently shut down by conservative governments not being complying with the local codes. However, comparing the actual border controls, police and military regulations in everyday life, the Web is still relatively open to everyone to join and participate[24], it provides many free nodes, software, resources. It has lots of potentials for commons, especially for sharing, distributing knowledge and engaging with one and another by means of various technical methods, including piracy via various distrusted file sharing sites.

In Knit++ we started with the question of creating a non-hieratical surface and decided to take knitting/weaving as the main conceptual framework for our web interface. In fact, when we compared the introduction of knitting /embroidery machines at the end of 19th century, we found great similarities with the introduction of personal computers and imaging technologies at the end of 20th century: knitting, weaving and sewing requires lines to be connected with each other in order to effectively render patterns. In both cases, technical procedures are embedded in systems of manufacturing; such as the type and speed of stitching and the color and thickness of yarn. All of these techniques need to be mastered by the worker, requiring considerable proficiency to carry out a pattern. Similar to stitches, knots and ties which forms a pattern over a fabric, electronic images are rendered by pixels (picture elements), which are projected on a monitor in order to “render” an image. A program interprets codes and generates an output to the screen. As opposed to knitting, which takes days to produce a pattern, the creation of images on a screen is instantly rendered. A media artist developing algorithmic procedures to produce various forms of images is similar to a worker generating a pattern on fabric, they have to master the either the code or software through which they are creating an output. A

When we started the project in 2002, we identified some problems with date-based archiving systems widely used by websites such as blogs or papers. Linear presentation methods creates hierarchies between the old and new content. In a date-based presentation system, every additional entry replaces an old one, which is practically pushed to the bottom and its presence is undermined. In order to eliminate both location and date-based linear presentation methods, we decided to create an open non-linear field. We specifically developed an online software in order to give unrestricted access to Knit++ members. When members uploaded their content, each entry is placed randomly on the navigation space and presented without any priority. The outcome of our investigation led to various images, videos and texts produced by members of collective. From the beginning to the end the idea of knitting was executed to sustain a complete project; all the works were about knitting, each project was placed like a knot (a node) and connected by the visitors, forming a flat digital topography, a constantly changing, evolving pattern.

“I was there” by pope (Guven Incirlioglu)

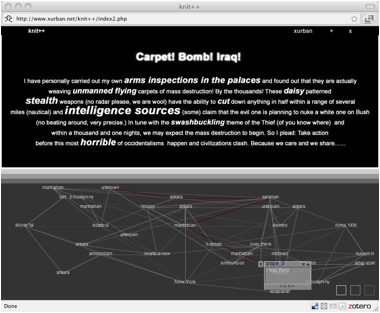

Many remarkable projects came out from our collective effort. For instance, kafir (Ali Demirel) and dublor (Alper Ersoy) developed an interactive flash video called “Knit the Carpet” in which they analyzed the movement and sound of the process of carpet weaving. When users interact with the video, the program automatically replaces patterns and sounds; an infinite looping and regeneration process reminds us that today’s DJ music culture or mash-up videos are effectively combining many different material together in a single piece. EA (Ceyda Karamursel) took a non-figurative approach and read an excerpt from Peter Handke’s “A Sorrow Beyond Dreams”, mixed with sounds from a woman’s gathering and a “housewife singing in her kitchen praying for her husband’s health and children’s success at school”. In a rather cynical shift, pope (Guven Incirlioglu), presented a piece of poetic writing called “Carpet! Bomb! Iraq!”, and took our attention to the war in Iraq where technical terms such as “carpet bombing” are utilized to designate a complete wipeout of a territory by means of large scale bombing aiming to smooth out any enemy target in a designating domain. His piece warned us about the naturalization of a military/state discourse, which aims to justify war based on ungrounded and fabricated facts about “weapons of mass destructions”.

But, What is wrong with Knitting?

“In striated space, lines or trajectories tend to be subordinated to points: one goes from one point to another. In smooth, it is the opposite: the points are subordinated to the trajectory”[25]

In one of his entries to Knit++, pope (Guven Incirlioglu) asked a daunting question; “Where do we go from here?”. Xurban_collective does not produce self-sufficient object for the art market. In each instance the project outcome need to be critically checked and evaluated. In fact, Knit++ was an experiment to test the idea of an alternative network, yet, we recognize that forms of a node/grid based networks are constantly created, utilized and often exploited by organizational structures to maximize their efficiency, reproduce and maintain order, including the military[26]. Certain forms of network theories are employed by think-tanks, policy makers, intelligence and marketing firms to find out most important node in the network, general trends and the ways and which agents are interacting with one another. “Horizontal” non-profit organizations do not necessarily producing an alternative either. In many “horizontal organizations”, hierarchies are embedded through effective subjectivation processes rather than top-to-bottom structural order, which makes it hard to identify symptoms. For instance, a worker’s involvement in decision-making processes does not suggest that they are actual contributors to the totality of decision-making, but it rather implies that factories require less managerial positions to get the job done. Within these organizational frameworks, involvement, engagement and participation becomes effective governmental strategies rather than new possibilities for alternative social arrangements.

Since the seven years that have we realized the project, we now see many multi-user websites; most of them geared towards generating income from the existence and growth of their network (online community). They actively utilize their user-base for their commercial interests. Although these networks -such as Facebook, Myspace- seem to be open and show many positive democratic features, their ultimate goal is to subsume human labor under capitalist processes. Users are transformed into dynamic participants of infinite consumption/production activities, therefore exploitation is embedded into the minute details of life in general. Here it is essential to revisit, Deleuze and Guattari’s conception of striated and smooth space once again;

“Smooth space and striated space—nomad space and sedentary space—the space in which the war machine develops and the space instituted by the State apparatus—are not of the same nature. No sooner do we note a simple opposition between the two kinds of space than we must indicate a much more complex difference by virtue of which the successive terms of the oppositions fail to coincide entirely”[27]

If smooth space is the space for alternative openings, striated space is the space of enclosure. The problem is that, in the Knit++ project, we did not make a precise distinction between different types of spaces. We made analogies with fabrication methods such as knitting, stitching, sewing, embroidery and weaving, but all of which are considered in a similar fashion. However, Deleuze and Guattari remind us that a successful task requires a deeper exploration between these technologies. A difference in a technical model can yield totally different results. If we aim to generate possibilities for new types of social interactions, we need to make precise distinctions between types of patterns, how they are produced and the natures of surfaces. In fact, if we look to current web2.0[28] sites examples such as Facebook, Google, Twitter or -- which allow relatively uninterrupted user participation -- we can identify that eventually these models create “striated spaces” in Deleuzian terms. Deleuze and Guattari warns us that we need to be aware of the fact that [military and corporate] state apparatus’ aim to enclose open domains and that there is a constant battle between tendency enclosures and passions for openings.

“Felt is a supple solid product that proceeds altogether differently, as an anti-fabric. It implies no separation of threads, no intertwining, only an entanglement of fibers obtained by fulling (for example, by rolling the block of fibers back and forth). What becomes entangled are the microscales of the fibers. An aggregate of intrication of this kind is in no way homogeneous: it is nevertheless smooth, and contrasts point by point with the space of fabric (it is in principle infinite, open, and unlimited in every direction; it has neither top nor bottom nor center; it does not assign fixed and mobile elements but rather distributes a continuous variation).”[29]

In a final evaluation, the next step for a similar project should aim to create a space that has similar properties to felt. On an infinite opening, each element, entry and user should come together by touching each other and forming a unity without actually linking with strict predefined technical parameters. A radical task to develop a smooth surface, like the sea, can provide many opportunities, including resisting properties to constant striatification. Openness requires an open technical framework which allows itself to be altered on the fly, it should allow errors and mistakes to be manifested, it should highlight both unity and contradiction without prioritizing one or another.

To solve these questions requires considerable social and technical efforts. Our next “network project” should address this fundamental question: how can we model such a new [social] machine? The answer lays beneath the social/technical formation of our collective existence. As Deleuze states, “machines are social before being technical”[30]. In order to develop an alternative network a considerable reexamination of our subjectivation processes as modern individuals is required, therefore we need to develop an idea of new social formations first so that we can model it technically.

[1] xurban_collective. “Knit++ // by xurban_collective //” http://www.xurban.net/scope/knit%2B%2B/index.htm

[2] For further information please visit http://www.xurban.net/notion/oncollectivity/index.html where xurban_collective discusses notion of collectivity and collective production.

[3] When we built the website in 2002, web 2.0 technologies were at their initial stages. Therefore our effort can be seen as a proto web 2.0, “"Web 2.0" is commonly associated with web development and web design that facilitates interactive information sharing, interoperability, user-centered design[1] and collaboration on the World Wide Web.” “Web 2.0 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0.

[4] Although the term interdisciplinary was excessively used and somewhat aged, for us, it was to key to bring forward different approaches for a salient conceptual strategy. As opposed to a professional conference or an exhibition which gathers similar profession together, we believe that a true interdisciplinary approached is required to have broader understanding.

[5] Jeffrey K. Liker and David Meier, Toyota Talent : Developing Your People the Toyota Way (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007).

[6] Lazzarato, M. “Immaterial labor.” Radical thought in Italy: A potential politics (1996): 133–50.

[7] International Labour Office, Social Protection of Homeworkers (Geneva: International Labor Organization, 1991).

[8] JONATHAN, FRIENDLY. “WORKING AT HOME; THE ELECTRONIC CHANGE: HOUSE BECOMES OFFICE - New York Times.” New York Times Online. http://www.nytimes.com/1986/05/15/garden/working-at-home-the-electronic-change-house-becomes-office.html?scp=4&sq=homeworker&st=nyt.

[9] Some of the famous examples include Steve Jobs of Apple Inc and Bill Gates of Microsoft, who were first started their business in home garages by providing services to bigger industries such as IBM.

[10] Annie Phizacklea and Carol Wolkowitz, Homeworking Women : Gender, Racism and Class at Work (London ; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1995), 31.

[11] Committee on Employment and Social Policy – International Labor Organization. “GB.274/ESP/4 - Governing Body.” http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/gb/docs/gb274/esp-4.htm#Homeworkers%20in%20the%20global%20economy:%20The%20Asian%20cr.

[12]International Labor Office, Social Protection of Homeworkers.

[13] For instance Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor report states that homeworking reaches to 15% of total non-agricultural employment in US.

Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor. “Work At Home in 2004 Summary.” http://www.bls.gov/news.release/homey.nr0.htm.

[14] S Allen and C Wolkowitz, Homeworking: Myths and Realities (MacMillan Education, Limited, 1987), 105.

[15] R Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (Basic Books, 1989), Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias : The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (New York: Basic Books, 1987).

[16] Phizacklea and Wolkowitz, Homeworking Women : Gender, Racism and Class at Work, 23.

[17] Mutari, E., H. Boushey, and W. Fraher. Gender and political economy: incorporating diversity into theory and policy. ME Sharpe Inc, 1997.

[18] Caroline Gatrell, Emboying Women's Work (New York: Open University Press, 2008), 147.

[19] Lazzarato, Maurizio. “Immaterial labor.” Radical thought in Italy: A potential politics (1996): 133–50.

[20] Sewing machines were invented in America in 1946 and exported to the UK in 1951; “THE SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN (September 22nd, 1860) considered that, after the Spinning Jenny and the plough, the sewing machine was 'the most important invention that has ever been made since the world began' ” (Joan Perkin. "Sewing machines: Liberation or drudgery for women?" History Today 52, no. 12 (December 1, 2002): 35-41. http://www.proquest.com.libproxy.newschool.edu/ (accessed September 28, 2009).

[21] Countries such as Iran, Turkey, Malaysia and Indonesia have a patriarchal morality that strongly emphasizes family life as the most important part of society. This compels women to remain in the domestic sphere. In this respect, in an Islamic society homeworking effectively works both with the patriarchal hierarchy and free market rules, providing the “best option” for the exploitation based on the sexual division of labor.

[22] Ghavamshahidi, "Homeworkers in Global Perspective : Invisible No More," ed. Eileen Boris and Elisabeth Prügl (New York: Routledge, 1996), 112.

[23] This oral traditions in fact mostly is taken out of historical processes because it was “women’s activity” happening in domestic sphere.

[24] Providing the fact that the user has necessary means to access technologies that allow them to be connected to the Internet. Since the price of those technical devises dropped considerably, and there are many public facilities (including internet cafés) providing the service, we can positively argue about its accessibility.

[25] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

[26] Military special operation units usual acts like self sustained independent groups to operate beyond enemy lines with no communication with headquarters, mimicking cell type militant organizations.

[27] Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

[28] “The term "Web 2.0" is commonly associated with web applications which facilitate interactive information sharing, interoperability, user-centered design[1] and collaboration on the World Wide Web. Examples of Web 2.0 include web-based communities, hosted services, web applications, social-networking sites, video-sharing sites, wikis, blogs, mashups and folksonomies.” Anon. Web 2.0 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0.

[29] Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus : Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 476.

[30] Gilles Deleuze and Seán Hand, Foucault (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).